Use it or lose it and getting it back.

Apologies to Robert Burns – let’s talk about where we are at week 4 of the lockdown.

Apologies to Robert Burns – let’s talk about where we are at week 4 of the lockdown.

Number of athletes getting a bit anxious about what is/will happen to their fitness given all their plans have gone awry.

This piece will focus on the physiology side of things (but not immune system) and keep an eye on the website as Di is going to do an article around mental resilience.

How quick you lose fitness depends on a whole host of factors, so the stuff I am going to refer to here are broad brush guidelines and yes, some of it will be a bit sports sciencey.

But for those that can’t be bothered reading on (Spoiler Alert for those that can) a rough rule of thumb it will take you between half the time to all of the time that you have missed – so if you have missed 12 weeks swimming expect that it will be 6-12 weeks before you feel your swim fitness return.

For those that have read on – Thank You.

Now don’t take my word for it, let’s have a look at some of the research behind detraining & retraining.

Detraining

Yes, it will happen – so let’s talk about some of the things that may be going up or going down.

Now you know better than anyone what happens when you stop or reduce areas of your training, so again Caveat Alert, I’m going to talk about the results from a general physiological perspective and some specific studies.

Sciencey bit – Within the lockdown period it would be anticipated that there would be decrease in Maximal oxygen uptake; blood volume; stroke volume during exercise; plus other cardiovascular reductions, as well as decreased lactate threshold, decreased glycogen storage and ability to use fat as a fuel source. Equally there will be an increase in Maximum heart rate, maximal respiratory exchange ratio (RER) plus a whole load of other stuff going on that ultimately mean a reduction in endurance performance. (1,2,3,4)

Sciencey bit – Within the lockdown period it would be anticipated that there would be decrease in Maximal oxygen uptake; blood volume; stroke volume during exercise; plus other cardiovascular reductions, as well as decreased lactate threshold, decreased glycogen storage and ability to use fat as a fuel source. Equally there will be an increase in Maximum heart rate, maximal respiratory exchange ratio (RER) plus a whole load of other stuff going on that ultimately mean a reduction in endurance performance. (1,2,3,4)

Speed tends to be the first thing that we lose…this is due to the reduction in motor units meaning that we have a reduction in muscle contraction. Type II fibres (fast twitch) are more effected by detraining that Type I. Type II tend to lose muscle fibre area (~6%) and isokinetic eccentric strength (~12%) in the first few weeks(5)

Expected endurance capacity loss will be around 7% in the first couple of weeks. The good news is that things tend to bottom out around the 56 day mark, where we would expect to see a reduction in VO2max in the region of 14-16%.(6,7)

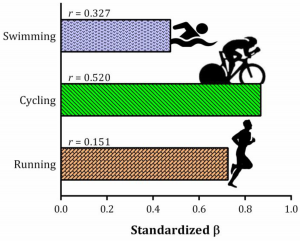

Now the big thing is that we can’t get in the pool and British Triathlon & Public Health England’s recommendations are that we don’t do any open water swimming – so how much swim fitness will we lose?

One recent study showed a 4% reduction in 400m swim TT time after 4 weeks of detraining.(8) So swimming is probably the area that may suffer most, given that athletes can still bike & run.

This is where the specificity of your training comes in – a 1990 study(9) of well-trained runners reduced their volume from ~80km per week down to ~25km per week. The key here was that even with a reduction in volume their VO2max remained the same as before as did their 5km time. Obviously, their endurance markers weren’t the same but they didn’t lose everything over the three week reduction in training as they kept the same training intensity.

Similarly Madsen et al (1993)(10)showed that five weeks training, taking runners from 10 hours training a week down to 1 x 35 minute session at a high intensity, ensured the runners maintained their VO2max but as you would expect their endurance capacity, the ability to run for an hour, was reduced by 21%

As a general rule of thumb higher end athletes will have a 2-4% drop off in cardiovascular, metabolic and neuromuscular responses per week.

But you don’t need the science to tell you how it feels, when it just feels a little bit off! That loss of rhythm, just not feeling it.

So how quickly will I get it back?

Transitions

Like all things in triathlon there is a Transition phase. Let’s look at the last four weeks as a sabbatical or transition.

It’s almost been like a taper into a race. If you were doing a 28 day taper you would probably look to reduce the volume by around 20-60% but keep your intensity high.(11)

Or view it as your recovery, post-event. Gale Bernhardt (US Olympic Coach) advocates 3-5 days recovery for every hour of a triathlon you race(12), so as you can see – the lockdown is giving us some great opportunities to refresh before re-training.

Now I’m sure you have managed some training and four weeks in is a good time to really get some structure back

Have a look back over your training pre-lockdown considering the volume & intensity. A lot of the training programmes I prescribe align with the 80/20 model(13) – I know there is an agreement for maybe having a 70/10/20 model but the point is, however your pre-lockdown training was structured you can still use that structure for the intensity you train at, just not the same volume! That routine will have a feel familiar to it.

Retraining – A little goes a long way! (Consistency trumps spectacular)

I know some athletes have been trying to fill their days and have jumped on 200km/6hr indoor bike rides but other than trying to fill days – what is the purpose? And that is the key Q.

I know some athletes have been trying to fill their days and have jumped on 200km/6hr indoor bike rides but other than trying to fill days – what is the purpose? And that is the key Q.

Where are your gaps?

When getting back into training let’s be sensible. Only doing 10-20% of your full-on volume will help you reduce your losses, so we can build from as low a base as that, but keeping the training intensity high is key(2,3)

If we do as little as 3 x 40 minutes exercise per week, that will half the reduction in our VO2max and power drop offs.(14)

One quick fix comes from some work done by the European Space Agency(15) – 3 minutes of Counter Movement Jumps (CMJ) done 6 times per week can minimize your VO2max drop off from 29% to only 5%. The same study showed that 3 minutes of CMJ reduces power losses from 29% to 12%. Big caution in doing jumps & hops if not used to plyometric work.

From a strength perspective, if you can’t get to the gym to get the big, heavy stuff then just train to failure, once or twice a week.(16,17)

Let’s round this out – as mentioned at the start – a rough rule of thumb is that whatever period of reduced or no training you have had, if you are being careful you can match that so 12 weeks off = 12 weeks build to get back, although it could be as little as half the time. 12 weeks off = 6 weeks build to get back.(18,19,20)

As it stands we are in lockdown in the UK until roundabout the week commencing Monday 4th May, for most of us that will be 6 weeks without access to swimming. If we could get back in the pool that week, in theory, that would mean it would be sometime between Saturday 24th May through until Saturday 13th June until we were swim fit again!

How does that fit in with your planned races?

Remember that the Synergie Coaches are about for online consultancy if you want to chat through your plans.

If you have some time on our hands these two are worth a watch

Ross Tucker https://youtu.be/ByD9HjJL554

Trent Stellingwerth https://youtu.be/Si3D6fImXOI

References

- Bompa, T., 0. (1999) Periodization: Theory & Methodology of Training. Human Kinetics. Champaign: IL.

- Mujika, I. & Padilla, S. (2000). Detraining: Loss of Training-Induced Physiological and Performance Adaptations. Part I. Sports medicine. 30. pp. 79-87.

- Tucker, R. (2020). Detraining in lockdown; Part 2. [Video webinar]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ByD9HjJL554

- Obert, P., et al (2003). Cardiovascular responses to endurance training in children: Effect of gender. European Journal of Clinical Investigations, 33 (3). pp. 199-208.

- Hortobagy, t., et al (1993). The effects of detraining on power athletes. Medicine of Sports Science and Exercise,

- Coyle, E., F. et al (1984). Time course of loss of adaptations after stopping prolonged intense endurance training. Journal of Applied Physiology, 57.

- McCardle, W., D., Katch, F., I., & Katch, V., L. (2001). Exercise Physiology: Energy, Nutrition, and Human Performance. Lippincote, Williams & Wilkins. Baltimore: MA.

- Zacca, R. et al. (2019). Effects of detraining in age group swimmers’ performance, energetics and kinematics. Journal of Sports Sciences.

- Houmard, J., A., et al (1990). Reduced training maintains performance in distance runners. International Journal of Sports Medicine, 11 (1), pp. 46-52.

- Madsen, K., et al (1993). Effects of detraining on endurance capacity and metabolic changes during prolonged exhaustive exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology, 75(4), pp. 1444-1451.

- Mujika, I. (2011). Tapering for triathlon competition. Journal of Human Sport & Exercise, 6 (2), pp.264-270.

- Roundtree, S. (2011). The athlete’s guide to recovery: Rest, relax & restore peak performance. Velo Press, Boulder: CO.

- Seiler, S. (2010). What is best practice for training intensity and duration distribution in endurance athletes? International Journal of Sports Physiology & Performance, pp. 276-291.

- Garcia-Pallares, J., et al (2010). Physiological effects of tapering and detraining in world-class kayakers. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 42 (6), pp 1209-1214.

- Klamer, A., et al (2017). High-Intensity Jump Training Is Tolerated during 60 Days of Bed Rest and Is Very Effective in Preserving Leg Power and Lean Body Mass: An Overview of the Cologne RSL Study. PLOS ONE 12(1): e0169793

- Burd, N., A, et al (2010). Low-load high volume resistance exercise stimulates muscle protein synthesis more than high-load low volume resistance exercise in young men. PLOS ONE 5(8): e12033

- Henwood, T., R., & Taaffe, D., R. (2008). Detraining and retraining in older adults following long-term muscle power or muscle strength specific training. The Journals of Gerontology; Series A, Biological Sciences & Medical Sciences. 63(7), pp. 751-758.

- Schoenfeld, B., et al (2019). Resistance Training Volume Enhances Muscle Hypertrophy but Not Strength in Trained Men. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 51(1), pp.94-103

- Blocquiaux, S., et al. (2020). The effect of resistance training, detraining and retraining on muscle strength and power, myofibre size, satellite cells and myonuclei in older men. Experimental Gerontology, 134.

- Staron, R., S., et al. (1991). Strength and skeletal muscle adaptations in heavy-resistance-trained women after detraining and retraining. Journal of Applied Physiology, 70(2).